Superquadrics Revisited

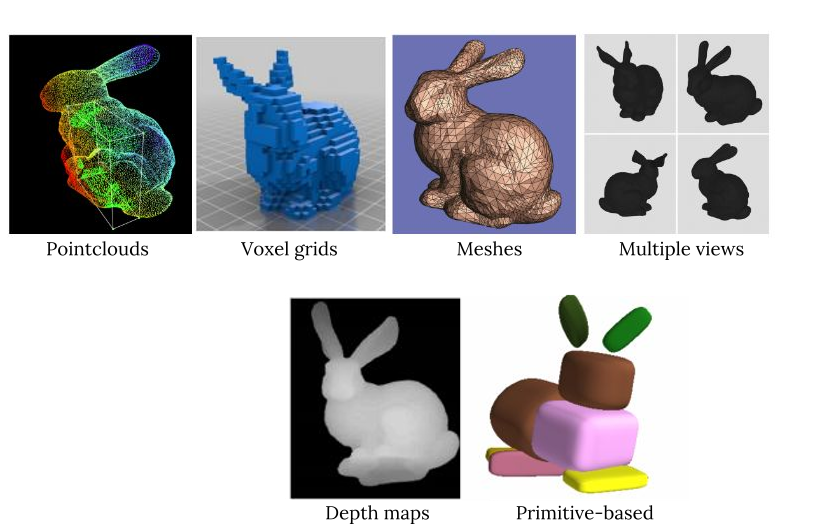

Recent advances in deep learning coupled with the abundance of large shape repositories gave rise to various methods that seek to learn the 3D model of an object directly from data. Based on the output representation these methods can be categorized into depth-based, voxel-based, point-based and mesh-based techniques. While all of these approaches are able to capture fine details, none of them directly yields a compact, memory-efficient and semantically meaningful representation.

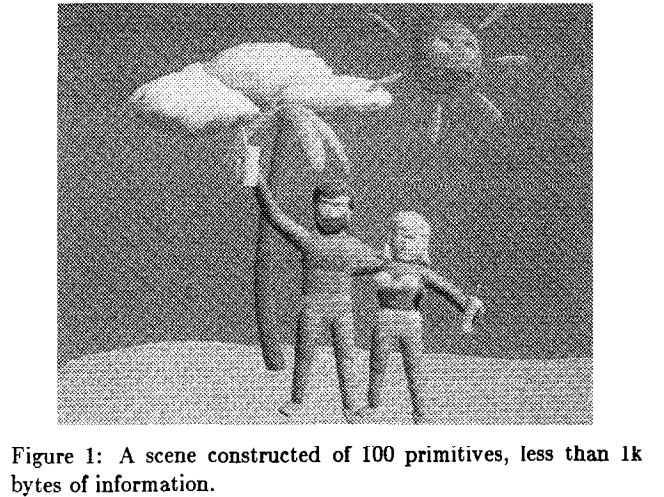

Inspired by the nature of the human’s cognitive system, that perceives an object as a decomposition of parts, researchers have proposed to represent objects as a set of atomic elements, which we refer to as primitives. Examples for such primitives include 3D polyhedral shapes, generalized cylinders and geons for decomposing 3D objects into a set of parts. In 1986, Pentland introduced a parametric version of generalized cylinders, based on deformable superquadrics, to the research community. He proposed a system able to represent the scene structure using multiple superquadrics.

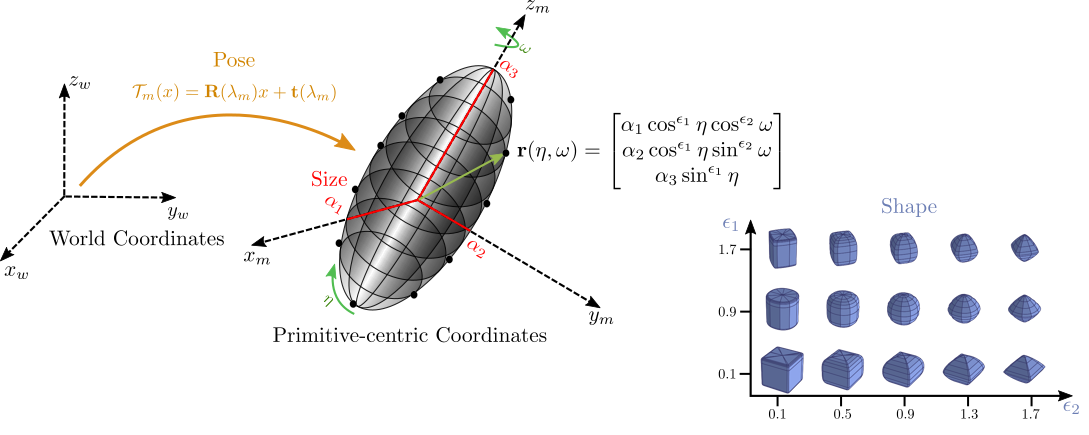

Superquadrics are a parametric family of surfaces that can be used to describe cubes, cylinders, spheres, octahedra, ellipsoids etc. Their continuous parametrization is particularly amenable to deep learning, as their shape is smooth and varies continuously with their parameters. They can be fully described using only 11 parameters: 6 for pose, 2 for shape and 3 for size.

However, early approaches for fitting primitive-based representations to input shapes remained largely unsuccessful due to the difficulty of optimizing the parameters for the input shape and achieving semantic consistency across instances. In our recent work Superquadrics Revisited: Learning 3D Shape Parsing beyond Cuboids, we lift superquadric representations to the deep era and try to answer the question of whether it is possible to train a neural network that recovers the geometry of a 3D object as a set of superquadrics from input images or 3D shapes in an unsupervised manner, namely without supervision in terms of the primitive parameters. As it turns out, unsupervised learning of primitive-based shape abstractions is not only feasible, but, compared to traditional fitting-based approaches, allows for exploiting semantic regularities across instances, leading to stable and semantically consistent predictions.

Our Approach

More formally, our goal is to learn a neural network

\[\phi_{\theta}: I \rightarrow P\]which maps an input representation \(I\) to a primitive representation \(P\), where \(P\) comprises the primitive parameters. As we used a fixed-dimensional output representation, we also predict the probability of existence for each primitive, indicating whether this primitive is part of the assembled object or not. This allows for inferring the number of primitives required to faithfully but compactly represent an object.

Despite the absence of supervision in terms of primitive annotations, one can still measure the discrepancy between the target and the predicted shape. Inspired by the work of Tulsiani et al. Learning Shape Abstractions by Assembling Volumetric Primitives, we formulate our optimization objective as the minimization of distances between points uniformly sampled from the surface of the target shape and the predicted shape:

\[L_D(P, X) = L_{P \rightarrow X}(P, X) + L_{X \rightarrow P}(X, P)\]- \(L_{P \rightarrow X}(P, X)\) measures the distance from the primitives P to the point cloud X and seeks to enforce precision.

- \(L_{X \rightarrow P}(X, P)\) measures the distance from the pointtlcoud X to the primitives P and seeks to enforce coverage.

For evaluating our loss, we sample points on the surface of each superquadric. This results in a stochastic approximator of the expected loss.

Does it work?

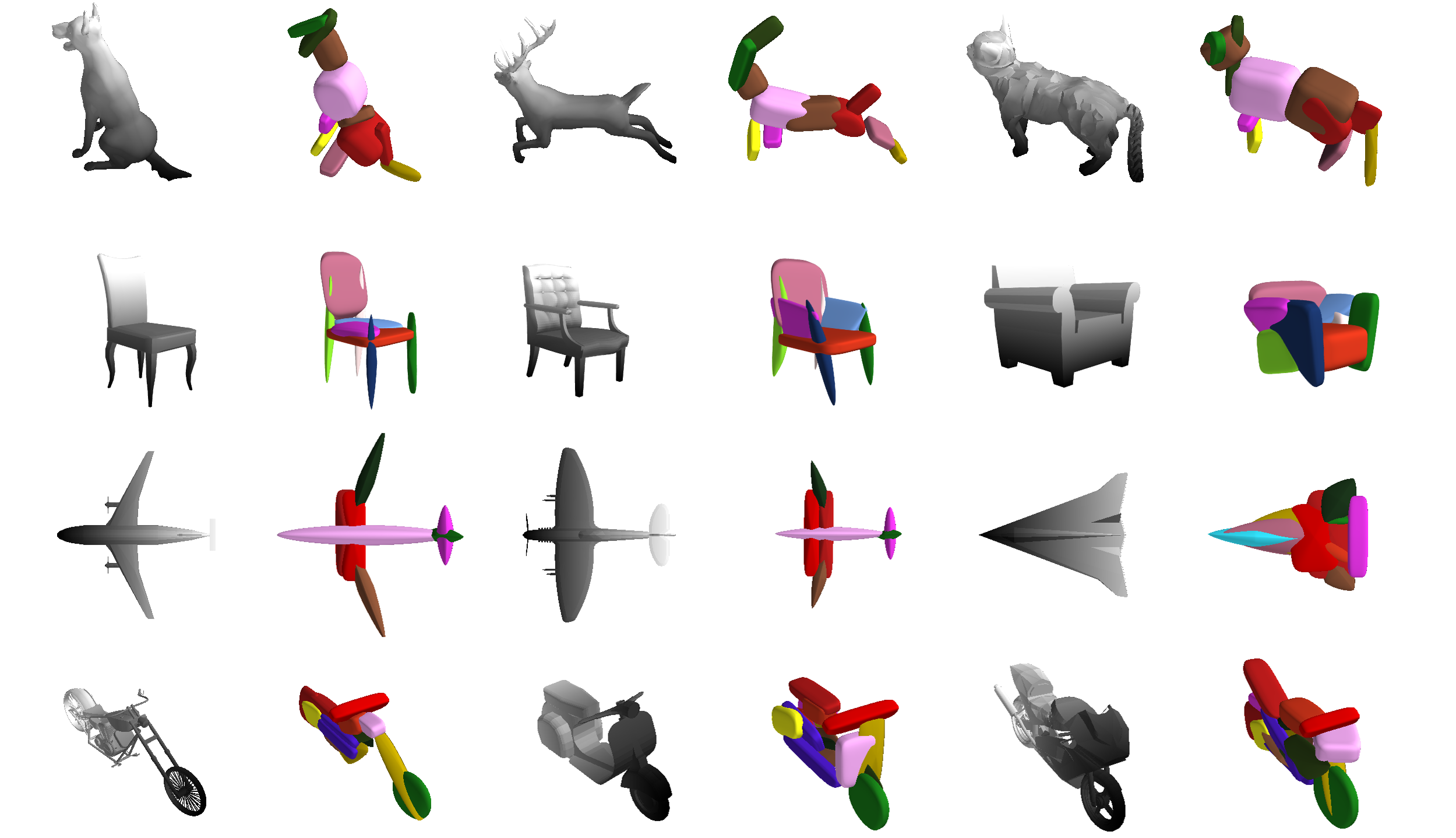

We conducted experiments that demonstrate that our model leads to expressive 3D shape abstractions that capture fine details such as the open mouth of the dog (left-most animal in first row) despite the lack of supervision. We observe that our shape abstractions allow for differentiating between different type of objects such as scooter, chopper, racebike by adjusting the shape of individual object parts. Another surprising property of our model is the semantic consistency of the predicted primitives: the same primitives (highlighted with the same color) consistently represents the same object part.

The diverse shape vocabulary of superquadrics allows us to recover more complicated shapes such as the human body under different poses and articulations. For instance, our model predicts pointy octahedral shapes for the feet, ellipsoidal shapes for the head and a flattened elongated superellipsoid for the main body without any supervision on the primitive parameters. Again, the same primitives (highlighted with the same color) consistently represent feet, legs, arms etc. across different poses.

Further Information

For more shape parsing results, check out this video:

Additional experiments can be found in our paper, our supplementary) and on our project page. If you are interested in experimenting with our model you can clone the code for this project from our github page.

@inproceedings{Paschalidou2019CVPR,

title = {Superquadrics Revisited: Learning 3D Shape Parsing beyond Cuboids},

author = {Paschalidou, Despoina and Ulusoy, Ali Osman and Geiger, Andreas},

booktitle = {Proceedings IEEE Conf. on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)},

year = {2019}

}